Congenital Heart Disease

Congenital (kon-JEN-i-tal) heart defects are problems with the heart's structure that are present at birth. These defects can involve:

- The interior walls of the heart

- The valves inside the heart

- The arteries and veins that carry blood to the heart or out to the body

Congenital heart defects change the normal flow of blood through the heart.

There are many types of congenital heart defects. They range from simple defects with no symptoms to complex defects with severe, life-threatening symptoms.

Congenital heart defects are the most common type of birth defect. They affect 8 of every 1,000 newborns. Each year, more than 35,000 babies in the United States are born with congenital heart defects.

Many of these defects are simple conditions that are easily fixed or need no treatment. A small number of babies are born with complex congenital heart defects that require special medical care soon after birth.

Over the past few decades, the diagnosis and treatment of these complex defects has greatly improved. As a result, almost all children who have complex heart defects survive to adulthood and can live active, productive lives.

Most people who have complex heart defects continue to need special heart care throughout their lives. They may need to pay special attention to how their condition may affect certain issues, such as health insurance, employment, pregnancy and contraception, and other health issues.

In the United States, about 1 million adults are living with congenital heart defects.

How the Heart Works

To understand congenital heart defects, it's helpful to know how a normal heart works. Your child's heart is a muscle about the size of his or her fist. It works like a pump and beats 100,000 times a day.

The heart has two sides, separated by an inner wall called the septum. The right side of the heart pumps blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen. Then, oxygen-rich blood returns from the lungs to the left side of the heart, and the left side pumps it to the body.

The heart has four chambers and four valves and is connected to various blood vessels. Veins are the blood vessels that carry blood from the body to the heart. Arteries are the blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart to the body.

A Healthy Heart Cross-Section

The illustration shows a cross-section of a healthy heart and its inside structures. The blue arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-poor blood flows from the body to the lungs. The red arrow shows the direction in which oxygen-rich blood flows from the lungs to the rest of the body.

Heart Chambers

The heart has four chambers or "rooms."

- The atria (AY-tree-uh) are the two upper chambers that collect blood as it comes into the heart.

- The ventricles (VEN-trih-kuls) are the two lower chambers that pump blood out of the heart to the lungs or other parts of the body.

Heart Valves

Four valves control the flow of blood from the atria to the ventricles and from the ventricles into the two large arteries connected to the heart.

- The tricuspid (tri-CUSS-pid) valve is in the right side of the heart, between the right atrium and the right ventricle.

- The pulmonary (PULL-mun-ary) valve is in the right side of the heart, between the right ventricle and the entrance to the pulmonary artery, which carries blood to the lungs.

- The mitral (MI-trul) valve is in the left side of the heart, between the left atrium and the left ventricle.

- The aortic (ay-OR-tik) valve is in the left side of the heart, between the left ventricle and the entrance to the aorta, the artery that carries blood to the body.

Valves are like doors that open and close. They open to allow blood to flow through to the next chamber or to one of the arteries, and then they shut to keep blood from flowing backward.

When the heart's valves open and close, they make a "lub-DUB" sound that a doctor can hear using a stethoscope.

- The first sound-the "lub"-is made by the tricuspid and mitral valves closing at the beginning of systole (SIS-toe-lee). Systole is when the ventricles contract, or squeeze, and pump blood out of the heart.

- The second sound-the "DUB"-is made by the pulmonary and aortic valves closing at the beginning of diastole (di-AS-toe-lee). Diastole is when the ventricles relax and fill with blood pumped into them by the atria.

Arteries

The arteries are major blood vessels connected to your heart.

- The pulmonary artery carries blood pumped from the right side of the heart to the lungs to pick up a fresh supply of oxygen.

- The aorta is the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood pumped from the left side of the heart out to the body.

- The coronary arteries are the other important arteries attached to the heart. They carry oxygen-rich blood from the aorta to the heart muscle, which must have its own blood supply to function.

Veins

The veins also are major blood vessels connected to your heart.

- The pulmonary veins carry oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to the left side of the heart so it can be pumped out to the body.

- The superior and inferior vena cavae are large veins that carry oxygen-poor blood from the body back to the heart.

For more information on how a healthy heart works, see the Diseases and Conditions Index article on How the Heart Works. This article contains animations that show how your heart pumps blood and how your heart's electrical system works.

Types of Congenital Heart Defects

Congenital heart defects change the normal flow of blood through the heart. This is because some part of the heart didn't develop properly before birth.

There are many types of congenital heart defects. Some are simple, such as a hole in the septum that allows blood from the left and right sides of the heart to mix, or a narrowed valve that blocks blood flow to the lungs or other parts of the body.

Other defects are more complex. These include combinations of simple defects, problems with where the blood vessels leading to and from the heart are located, and more serious problems with how the heart develops.

Examples of Simple Congenital Heart Defects

Holes in the Heart (Septal Defects)

The septum is the wall that separates the chambers on the left side of the heart from those on the right. The wall prevents mixing of blood between the two sides of the heart. Sometimes, a baby is born with a hole in the septum. The hole allows blood to mix between the two sides of the heart.

Atrial septal defect (ASD). An ASD is a hole in the part of the septum that separates the atria-the upper chambers of the heart. This heart defect allows oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium to flow into the right atrium instead of flowing to the left ventricle as it should. Many children who have ASDs have few, if any, symptoms.

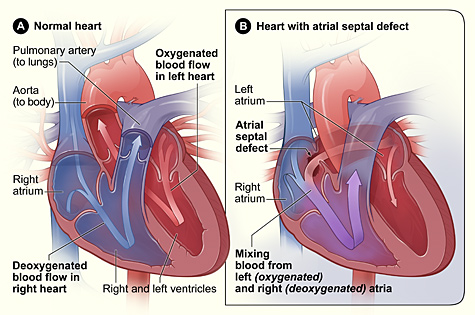

Normal Heart and Heart With Atrial Septal Defect

Figure A shows the structure and blood flow in the interior of a normal heart. Figure B shows a heart with an atrial septal defect, which allows oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium to mix with oxygen-poor blood from the right atrium.

An ASD can be small or large. Small ASDs allow only a little blood to leak from one atrium to the other. Very small ASDs don't affect the way the heart works and don't require any treatment. Many small ASDs close on their own as the heart grows during childhood.

Medium to large ASDs allow more blood to leak from one atrium to the other, and they're less likely to close on their own.

Half of all ASDs close on their own or are so small that no treatment is needed. Medium to large ASDs that need treatment can be repaired using a catheter procedure or open-heart surgery.

Ventricular septal defect (VSD). A VSD is a hole in the part of the septum that separates the ventricles-the lower chambers of the heart. The hole allows oxygen-rich blood to flow from the left ventricle into the right ventricle instead of flowing into the aorta and out to the body as it should.

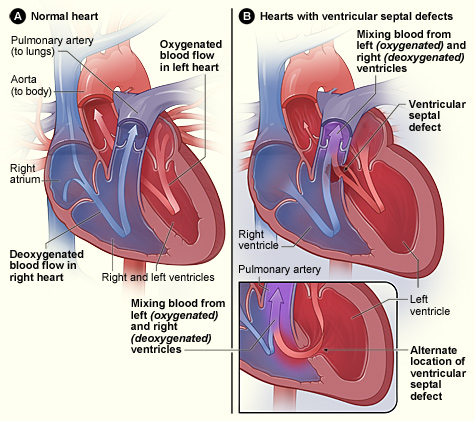

Normal Heart and Heart With Ventricular Septal Defect

Figure A shows the structure and blood flow in the interior of a normal heart. Figure B shows two common locations for a ventricular septal defect. The defect allows oxygen-rich blood from the left ventricle to mix with oxygen-poor blood in the right ventricle.

A VSD can be small or large. A small VSD doesn't cause problems and may close on its own. Large VSDs cause the left side of the heart to work too hard. This increases blood pressure in the right side of the heart and the lungs because of the extra blood flow.

The increased work of the heart can cause heart failure and poor growth. If the hole isn't closed, high blood pressure can scar the delicate arteries in the lungs. Open-heart surgery is used to repair VSDs.

Narrowed Valves

Simple congenital heart defects also can involve the heart's valves. These valves control the flow of blood from the atria to the ventricles and from the ventricles into the two large arteries connected to the heart (the aorta and the pulmonary artery). Valves can have the following types of defects:

- Stenosis (ste-NO-sis). This defect occurs if the flaps of a valve thicken, stiffen, or fuse together. This prevents the valve from fully opening. The heart has to work harder to pump blood through the valve.

- Atresia (a-TRE-ze-AH). This defect occurs if a valve doesn't form correctly and lacks a hole for blood to pass through. Atresia of a valve generally results in more complex congenital heart disease.

- Regurgitation (re-GUR-ji-TA-shun). This is when the valve doesn't close completely, so blood leaks back through the valve.

The most common valve defect is called pulmonary valve stenosis, which is a narrowing of the pulmonary valve. This valve allows blood to flow from the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery. From there it flows to the lungs to pick up oxygen.

Pulmonary valve stenosis can range from mild to severe. Most children who have this defect have no signs or symptoms other than a heart murmur. (A heart murmur is an extra or unusual sound heard during a heartbeat.) Treatment isn't needed if the stenosis is mild.

In babies who have severe pulmonary valve stenosis, the right ventricle can get very overworked trying to pump blood to the pulmonary artery. These infants may have symptoms such as rapid or heavy breathing, fatigue (tiredness), or poor feeding.

If a baby also has an ASD or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), oxygen-poor blood can flow from the right side of the heart to the left side. This can cause cyanosis (si-a-NO-sis). Cyanosis is a bluish tint to the skin, lips, and fingernails. It occurs because the oxygen level in the blood leaving the heart is below normal.

Older children who have severe pulmonary valve stenosis may have symptoms such as fatigue while exercising. Severe pulmonary valve stenosis is treated with a catheter procedure.

Example of a Complex Congenital Heart Defect

Complex congenital heart defects need to be repaired with surgery. Because of advances in diagnosis and treatment, doctors can now successfully repair even very complex congenital heart defects.

The most common complex heart defect is tetralogy of Fallot (teh-TRAL-o-je of fah-LO), a combination of four defects:

- Pulmonary valve stenosis.

- A large VSD.

- An overriding aorta. In this defect, the aorta sits above both the left and right ventricles over the VSD, rather than just over the left ventricle. As a result, oxygen-poor blood from the right ventricle can flow directly into the aorta instead of into the pulmonary artery to the lungs.

- Right ventricular hypertrophy. In this defect, the muscle of the right ventricle is thicker than usual because of having to work harder than normal.

Together, these four defects mean that not enough blood is able to reach the lungs to get oxygen, and oxygen-poor blood flows out to the body.

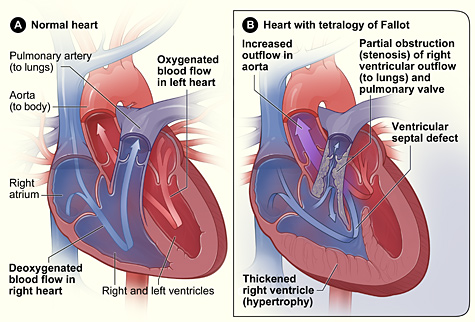

Normal Heart and Heart With Tetralogy of Fallot

Figure A shows the structure and blood flow in the interior of a normal heart. Figure B shows a heart with the four defects of tetralogy of Fallot.

Babies and children who have tetralogy of Fallot have episodes of cyanosis, which can sometimes be severe. In the past, when this condition wasn't treated in infancy, older children would get very tired during exercise and could have fainting spells. Tetralogy of Fallot is now repaired in infancy to prevent these types of symptoms.

Tetralogy of Fallot must be repaired with open-heart surgery, either soon after birth or later in infancy. The timing of the surgery will depend on how much the pulmonary artery is narrowed.

Children who have had this heart defect repaired need lifelong medical care from a specialist to make sure they stay as healthy as possible.

Other Names for Congenital Heart Defects

- Congenital heart disease

- Heart defects

- Congenital cardiovascular malformations

What Causes Congenital Heart Defects?

If you have a child who has a congenital heart defect, you may think you did something wrong during your pregnancy to cause the problem. However, most of the time doctors don't know why congenital heart defects develop.

Heredity may play a role in some heart defects. For example, a parent who has a congenital heart defect may be more likely than other people to have a child with the condition. In rare cases, more than one child in a family is born with a heart defect.

Children who have genetic disorders, such as Down syndrome, often have congenital heart defects. In fact, half of all babies who have Down syndrome have congenital heart defects.

Smoking during pregnancy also has been linked to several congenital heart defects, including septal defects.

Scientists continue to search for the causes of congenital heart defects.

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Congenital Heart Defects?

Many congenital heart defects have few or no signs or symptoms. A doctor may not even detect signs of a heart defect during a physical exam.

Some heart defects do have signs and symptoms. They depend on the number, type, and severity of the defects. Severe defects can cause signs and symptoms, usually in newborns. These signs and symptoms may include:

- Rapid breathing

- Cyanosis (a bluish tint to the skin, lips, and fingernails)

- Fatigue (tiredness)

- Poor blood circulation

Congenital heart defects don't cause chest pain or other painful symptoms.

Heart defects can cause abnormal blood flow through the heart that will make a certain sound called a heart murmur. Your doctor can hear a heart murmur with a stethoscope. However, not all murmurs are signs of congenital heart defects. Many healthy children have heart murmurs.

Normal growth and development depend on a normal workload for the heart and normal flow of oxygen-rich blood to all parts of the body. Babies who have congenital heart defects may have cyanosis and/or tire easily when feeding. As a result, they may not gain weight or grow as they should.

Older children who have congenital heart defects may get tired easily or short of breath during physical activity.

Many types of congenital heart defects cause the heart to work harder than it should. In severe defects, this can lead to heart failure. Heart failure is a condition in which the heart can't pump enough blood to meet the body's needs. Symptoms of heart failure include:

- Fatigue with physical activity

- Shortness of breath

- A buildup of blood and fluid in the lungs

- A buildup of fluid in the feet, ankles, and legs

How Are Congenital Heart Defects Diagnosed?

Severe congenital heart defects are generally found during pregnancy or soon after birth. Less severe defects aren't diagnosed until children are older.

Minor defects often have no signs or symptoms and are diagnosed based on results from a physical exam and tests done for another reason.

Specialists Involved

Doctors who specialize in the care of babies and children who have heart problems are called pediatric cardiologists. Cardiac surgeons are other specialists who treat heart defects. These doctors repair heart defects using surgery.

Physical Exam

During a physical exam, the doctor will:

- Listen to your child's heart and lungs with a stethoscope

- Look for signs of a heart defect, such as cyanosis (a bluish tint to the skin, lips, or fingernails), shortness of breath, rapid breathing, delayed growth, or signs of heart failure

Diagnostic Tests

Echocardiography

Echocardiography (echo) is a painless test that uses sound waves to create a moving picture of the heart. During the test, the sound waves (called ultrasound) bounce off the structures of the heart. A computer converts the sound waves into pictures on a screen.

Echo allows the doctor to clearly see any problem with the way the heart is formed or the way it's working.

Echo is an important test for both diagnosing a heart problem and following the problem over time. In children who have congenital heart defects, echo can show problems with the heart's structure and how the heart is reacting to these problems. Echo will help your child's cardiologist decide if and when treatment is needed.

During pregnancy, if your doctor suspects that your baby has a congenital heart defect, a fetal echo can be done. This test uses sound waves to create a picture of the baby's heart while the baby is still in the womb.

The fetal echo usually is done at about 18 to 22 weeks of pregnancy. If your child is diagnosed with a congenital heart defect before birth, your doctor can plan treatment before the baby is born.

EKG (Electrocardiogram)

An EKG is a simple, painless test that records the heart's electrical activity. The test shows how fast the heart is beating and its rhythm (steady or irregular). It also records the strength and timing of electrical signals as they pass through each part of the heart.

An EKG can detect if one of the heart's chambers is enlarged, which can help diagnose a heart problem.

Chest X Ray

A chest x ray is a painless test that creates pictures of the structures in the chest, such as the heart and lungs. This test can show whether the heart is enlarged or whether the lungs have extra blood flow or extra fluid, a sign of heart failure.

Pulse Oximetry

Pulse oximetry shows how much oxygen is in the blood. For this test, a small sensor is attached to a finger or toe (like an adhesive bandage). The sensor gives an estimate of how much oxygen is in the blood.

Cardiac Catheterization

During cardiac catheterization (KATH-e-ter-i-ZA-shun), a thin, flexible tube called a catheter is put into a vein in the arm, groin (upper thigh), or neck and threaded to the heart.

Special dye is injected through the catheter into a blood vessel or a chamber of the heart. The dye allows the doctor to see the flow of blood through the heart and blood vessels on an x-ray image.

The doctor also can use cardiac catheterization to measure the pressure and oxygen level inside the heart chambers and blood vessels. This can help the doctor determine whether blood is mixing between the two sides of the heart.

Cardiac catheterization also is used to repair some heart defects.

How Are Congenital Heart Defects Treated?

Although many children who have congenital heart defects don't need treatment, some do. Doctors repair congenital heart defects with catheter procedures or surgery.

The treatment your child receives depends on the type and severity of his or her heart defect. Other factors include your child's age, size, and general health.

Some children who have complex congenital heart defects may need several catheter or surgical procedures over a period of years, or they may need to take medicines for years.

Catheter Procedures

Catheter procedures are much easier on patients than surgery because they involve only a needle puncture in the skin where the catheter (thin, flexible tube) is inserted into a vein or an artery.

Doctors don't have to surgically open the chest or operate directly on the heart to repair the defect(s). This means that recovery may be easier and quicker.

The use of catheter procedures has grown a lot in the past 20 years. They have become the preferred way to repair many simple heart defects, such as atrial septal defect (ASD) and pulmonary valve stenosis.

For an ASD, the doctor inserts a catheter through a vein and threads it into the heart to the septum. The catheter has a tiny, umbrella-like device folded up inside it.

When the catheter reaches the septum, the device is pushed out of the catheter. It's positioned so that it plugs the hole between the atria. The device is secured in place and the catheter is then withdrawn from the body.

For pulmonary valve stenosis, the doctor inserts a catheter through a vein and threads it into the heart to the pulmonary valve. A tiny balloon at the end of the catheter is quickly inflated to push apart the leaflets, or "doors," of the valve. The balloon is then deflated and the catheter and ballon are withdrawn. This procedure can be used to repair any narrowed valve in the heart.

To help guide the catheter, doctors often use echocardiography (echo) or transesophageal (tranz-ih-sof-uh-JEE-ul) echocardiography (TEE) and angiography (an-jee-OG-ra-fee).

TEE is a special type of echo that takes pictures of the back of the heart through the esophagus (the passage leading from the mouth to the stomach). TEE also is often used to examine complex heart defects.

Doctors also sometimes combine catheter and surgical procedures to repair complex heart defects, which may involve several kinds of defects.

Surgery

A child may need open-heart surgery if his or her heart defect can't be fixed using a catheter procedure. Sometimes, one surgery can repair the defect completely. If that's not possible, the child may need more surgeries over months or years to fix the problem.

Open-heart surgery may be done to:

- Close holes in the heart with stitches or with a patch

- Repair or replace heart valves

- Widen arteries or openings to heart valves

- Repair complex defects, such as problems with where the blood vessels near the heart are located or how they developed

Rarely, babies are born with multiple defects that are too complex to repair. These babies may need heart transplants. In this procedure, the child's heart is replaced with a healthy heart from a deceased child that has been donated by that child's family.

Living With a Congenital Heart Defect

The outlook for a child who has a congenital heart defect is much better today than in the past. Advances in testing and treatment mean that most children who have heart defects survive to adulthood and are able to live active, productive lives.

Many of these children need only occasional checkups with a cardiologist (heart specialist) as they grow up and go through adult life.

Children who have complex heart defects need long-term, special care by trained specialists. This will help them stay as healthy as possible and maintain a good quality of life.

Children and Teens

Ongoing Medical Care

Ongoing medical care is important for your child's health. This includes:

- Checkups with your child's heart specialist as directed

- Routine exams with your child's pediatrician or family doctor

- Taking medicines as prescribed

Children who have severe heart defects may be at slightly increased risk for infective endocarditis (IE). IE is a serious infection of the inner lining of your heart chambers and valves.

In a few situations, your child's doctor or dentist may give your child antibiotics before medical or dental procedures (such as surgery or dental cleanings) that could allow bacteria into the bloodstream. Your child's doctor will tell you whether your child needs to take antibiotics before such procedures.

To reduce the risk of IE, gently brush your young child's teeth every day as soon as they begin to come in. As your child gets older, make sure he or she brushes every day and sees a dentist regularly. Talk with your child's doctor and dentist about how to keep your baby or child's mouth and teeth healthy.

As children who have heart defects grow up and become teens, it's important that they understand what kind of defect they have, how it was treated, and what kind of care is still needed.

This understanding will help these teens take responsibility for their health. It also will help ensure a smooth transition when they start getting care from a cardiologist instead of a pediatric cardiologist. A cardiologist treats adults who have heart problems.

Young adults who have complex congenital heart defects require ongoing care by doctors who specialize in adult congenital heart disease.

You may want to work with your health care providers to put together a packet of medical records and information that covers all aspects of your child's heart defect, including:

- Diagnosis

- Procedures or surgeries

- Prescribed medicines

- Recommendations about medical followup and how to prevent complications

- Health insurance

Keeping your health insurance current is important. For example, if you plan to change jobs, find out whether your new health insurance will cover care for your child's congenital heart defect. Some health insurance plans may not cover medical conditions that were covered under a previous plan.

It's also very important for your child to have health insurance as adulthood approaches. Review your current health insurance plan. Find out how you can extend coverage to your child beyond the age of 18. Some policies may allow you to keep your child on your plan if he or she remains in school or is disabled.

Feeding and Nutrition

Some babies and children who have congenital heart defects don't grow and develop as fast as other children. If your child's heart has to pump harder than normal because of a heart defect, he or she may tire quickly when feeding or eating and not be able to eat enough.

As a result, your child may be smaller and thinner than other children. Your child also may start certain activities, such as rolling over, sitting, and walking, later than other children. After treatments and surgery, growth and development often improve.

To help your baby get enough calories, talk to his or her doctor about the best feeding schedule and any nutritional supplements your baby may need. Make sure your child has nutritious meals and snacks as he or she grows. This will help with growth and development.

Physical Activity

Physical activity helps children strengthen their muscles and stay healthy. Discuss with your child's doctor how much and what kinds of physical activity are best for your child. Some children and teens who have congenital heart defects may need to limit the amount or type of activity they do.

Remember to ask the doctor for a note for school and other organizations that describes any limits on your child's physical activities.

Emotional Issues

It's common for children and teens who have serious conditions or illnesses to have a hard time emotionally or to feel isolated if they have to be in the hospital a lot.

Some feel sad or frustrated with their body image and their inability to be a "normal" kid. Sometimes brothers or sisters are jealous of a child who needs a lot of attention for medical problems.

If you have concerns about your child's emotional health, talk to his or her doctor.

Adults

Adults who needed regular medical checkups for congenital heart defects in their youth may need to keep seeing specialists who can care for their health. These adults should pay attention to the following issues.

Medical History

Some people believe that the surgery they had in childhood for their congenital heart defects was a cure. They don't realize that regular medical followup may be needed in adulthood to maintain good health.

Some adults may not know what kind of heart defect they had (or still have) or how it was repaired. They should learn about their medical history and know as much as possible about any medicines they're taking.

Preventing Infective Endocarditis

In a few situations, people who have congenital heart defects may need antibiotics before medical or dental procedures that could allow bacteria to enter the bloodstream.

Your doctor will tell you whether you need to take antibiotics before such procedures. Regular brushing, flossing, and visits to the dentist also can help prevent IE.

Contraception and Pregnancy

Women who have heart defects should talk with their doctors about the safest type of birth control for them. Many women can safely use most methods. However, some women should avoid certain types of birth control, such as birth control pills or intrauterine devices (IUDs).

Many women who have simple heart defects can have a normal pregnancy and delivery. Women with congenital heart defects who want to become pregnant (or who are pregnant) should talk with their doctors about the health risks. They also should consult with doctors who specialize in treating pregnant women who have congenital heart defects.

Women who have congenital heart defects may be at higher risk than other women of having babies who have congenital heart defects.

Pregnant women who have congenital heart defects should talk with their doctors about whether to have fetal echocardiography (echo). This test uses sound waves to create images of the baby's heart.

Fetal echo gives the doctor information about the size and shape of the baby's heart and how well the chambers and valves are working.

Health Insurance and Employment

When thinking about changing jobs, adults who have congenital heart defects should carefully consider how it will affect their health insurance coverage.

Some health plans have waiting periods or clauses to exclude some kinds of coverage. Before making any job changes, find out whether the change will affect your health insurance coverage.

Several laws protect the employment rights of people who have health conditions, such as congenital heart defects. The Americans with Disabilities Act and the Work Incentives Improvement Act try to ensure fairness in hiring for all people, including those who have health conditions.

Key Points

- Congenital heart defects are problems with the heart's structure that are present at birth. These defects can involve the interior walls of the heart, the valves inside the heart, or the arteries and veins that carry blood to the heart or out to the body. Congenital heart defects change the normal flow of blood through the heart.

- Congenital heart defects are the most common type of birth defect. They affect 8 out of every 1,000 newborns. Each year, more than 35,000 babies in the United States are born with congenital heart defects.

- There are many types of congenital heart defects. They range from simple defects with no symptoms to complex defects with severe, life-threatening symptoms.

- Doctors don't know what causes most congenital heart defects. Heredity may play a role. Also, children who have genetic disorders, such as Down syndrome, often have congenital heart defects. Smoking during pregnancy also has been linked to several congenital heart defects.

- Although many congenital heart defects have few or no symptoms, some do. Severe defects can cause signs and symptoms such as:

- Rapid breathing

- Cyanosis (a bluish tint to skin, lips, and fingernails)

- Fatigue (tiredness)

- Poor blood circulation

- Congenital heart defects also may cause heart murmurs and delayed growth and development. Severe heart defects can lead to heart failure.

- Severe heart defects generally are found during pregnancy or soon after birth. Less severe defects aren't diagnosed until children are older. Echocardiography is an important test for both diagnosing a heart problem and following the problem over time. Other tests also may be used to help diagnose congenital heart defects.

- Although many children who have congenital heart defects don't need treatment, some do. Doctors repair heart defects with catheter procedures or surgery. The treatment your child receives depends on the type and severity of his or her heart defect. Other factors include your child's age, size, and general health.

- With new advances in testing and treatment, most children who have congenital heart defects survive to adulthood and can lead healthy, productive lives. Some need special care throughout their lives to maintain a good quality of life.